The Definitive Guide to Focus Groups in Business Analysis

/I got to watch Silicon Valley on HBO last month – all four seasons of it.

Time well spent.

The show is a wonderful and humorous view into software product management. And it has some great depictions of focus groups. Here’s one:

But here’s the deal. We know that focus groups are a method available to us (see BABOK v3 section 10.21). But we Business Analysts know very little about when, why, and how to run them.

And a lot of what people have written is plain wrong.

Like the Hooli phone, this situation is “messed up.”

In this article, we’ll step through:

What focus groups are,

When (and when not) to run them

Review some example scenarios

And then, over the next couple posts, we’ll look at:

How to plan focus groups

How to recruit participants

How to run them

How to analyze the data focus groups produce

How to report on focus group results

By the end, you will be an expert.

What a focus group is

So, what is a focus group anyway?

Oxford Dictionary defines it as “…A demographically diverse group of people assembled to participate in a guided discussion about a particular product before it is launched, or to provide ongoing feedback on a political campaign, television series, etc.”

This is a good definition. Let’s dissect it.

First, we are meeting with a “demographically diverse group of people.”

In the business analysis context, these groups are customers. Or users or employees or salespeople or whomever we want to learn from.

Within the broad populations we select, we don’t target further. We want a roughly random sampling that is representative of the larger population.

So if we want to learn about commuters, we would include a wide sampling of that group (not only bus commuters).

Second, it’s a “guided discussion.”

The moderator of the group is asking questions, and the participants respond. Participants are also free to interact with each other and respond to others.

Not only is it a guided discussion, but it's also a carefully planned one. There is a finely-tuned set of questions designed to bring out the best possible information.

Finally, we’re looking for feedback.

As Business Analysts, we don't care how people feel about political campaigns or television shows.

We use focus groups to learn how users feel about a system, prototype, strategy, business trend, or any of a dozen other things that we need feedback on.

This is a fine definition, but there is a missing piece. BABOK v3 contributes: “A focus group is a means to elicit ideas and opinions about a specific product, service, or opportunity in an interactive group environment. The participants, guided by a moderator, share their impressions, preferences, and needs.”

The purpose of the focus group is to get impressions, feelings, sentiments. All the mushy stuff. They provide rich qualitative information about how people feel and think.

When to run a focus group

Given this definition, some aspects of when to run a focus group are clear.

Since focus groups center on participants’ sentiments, we won’t use them to draw out detailed requirements or product ideas.

There are better tools for those purposes (e.g. interviews, brainstorming sessions).

And since focus groups produce qualitative information, we won’t use them when we need precise data.

Let's say you are trying to learn about the attitudes of potential customers. And there are 10,000 people in that population.

If seven out of ten focus group participants say they like your product, that sounds great. But the 70% “like rate” is misleading, because the margin of error is a massive 25%. Anywhere from 45% to 95% of the 10,000 customers will like your product.

A standard margin of error of 3% requires 964 responses, far more than focus groups will deliver.

A better tool for this type of quantitative data would be a survey (and one with a very high response rate).

We should only use focus groups when we have enough time to run them the right way. (Later in this blog series, we’ll see that focus groups are projects unto themselves. They are hard to run within the confines of a typical project’s analysis phase.)

Let’s look at a scenario where focus groups proved invaluable.

Scenario: "Alpha" Power & Light's Rate Increase

In “Applications of Focus Group Interviews in Marketing,” Cox et al. describe the real-life situation of Alpha Power & Light (pseudonym). They wanted to understand what customers thought about a possible electricity rate increase. And they needed to know why customers might be resistant to it.

They developed a three-stage plan:

In stage one, researchers would interview management and employees. They would also review firm information to come up with an initial internal view

In stage two, they would conduct 12 focus groups with 10 participants each. The goal would be to get high-level customer sentiment about the increase

In stage three, they would run a 700-customer survey to quantify what they learned

There is a lot to learn here:

Focus groups make sense as part of a larger research or elicitation study.

In a business analysis context, we shouldn’t expect focus groups to provide much requirement information.

Instead, we should use them to develop a general layout of user sentiment that informs our more detailed future work.

We run focus groups early in research.

Alpha conducted their focus groups immediately after internal stakeholder interviews and documentary research. This is akin to the pre-analysis phase of a project.

A single focus group is not enough.

The most common practice (see Thackeray & Neiger) is to conduct focus groups until they stop producing new information.

This rarely happens in fewer than three iterations (although planning twelve groups does seem to surpass the average).

Alpha Power & Light effectively used focus groups to steer its market research efforts. Indeed, this is one of the most common uses of focus groups.

But they can also serve as a perfect method for business analysis contexts. Some hypothetical business analysis projects will help to illustrate this.

Project 1: Re-engineering a system

Imagine a new project to redesign a company’s proprietary CRM system.

Management’s goals for the system are to...

Increase sales

Improve the customer experience

Reduce the cost of the sales function

In an interview with the project sponsor, you delve into the second goal. You ask how the CRM system will improve the customer experience.

She says that the customer experience is disjointed. Customers are inconsistently communicated with. And the relationship management teams miss a large number of service opportunities.

She goes on to say, “there are probably a lot of other things out there that we don’t even know about.”

Will focus groups make sense in this situation? Yes.

At this earliest stage in the project, you are facing maximum uncertainty. Management has identified a set of problems, but it's unclear how they impact the firm and its clients.

Focus groups aimed at learning how customers feel about the firm, its service, and its products can provide direction here. And that information will help steer the project, success criteria, and requirements development.

Project 2: Assessing the business case for a process redesign

Consider another effort where an airport wishes to increase passenger satisfaction. They want to substantially reduce the length of time it takes to get to their gates.

Systems will play a role. But management expects the core improvements to come from simpler processes. They also suspect that better communication with passengers and airlines will help.

You need to understand the problems passengers run into between entering the airport and arriving at their gate.

Does a focus group make sense in this situation? Probably not.

Since you need detailed information, interviews make more sense. Interviews demand less time and effort than focus groups, and yield more detailed information.

Free-form interviews also give you more freedom to branch off in promising new directions. Focus groups follow a predefined set of questions.

But if you wanted to understand how passengers felt about the time-to-gate problem – or even if it was a problem at all – focus groups could be a good fit.

Project 3: Determining priorities for a product road map

Finally, consider a pre-project analysis effort.

As part of a product development team, you are designing a smartphone app to help users curb bad habits. Your task is to determine priorities among a list of 30 possible features.

Pure analysis has not yielded a definitive list of priorities. And you don’t have enough data about user preferences and habits to make an educated guess.

Management’s goal is to have a strong initial launch with solid reviews. And that will mean making a big difference in the lives of the users.

Do focus groups make sense in this situation? Yes, they do.

The lack of knowledge about users is a strong sign that qualitative research is necessary.

User interviews could be a good approach. But at this exploratory stage, focus groups provide the opportunity to systematically investigate the users and what’s important to them.

Once the focus groups are complete, you could turn to more qualitative methods like surveys. Or you could dive deeper with interviews to flesh out the data needed to come up with a prioritized road map.

PLANNING: How to design a focus group

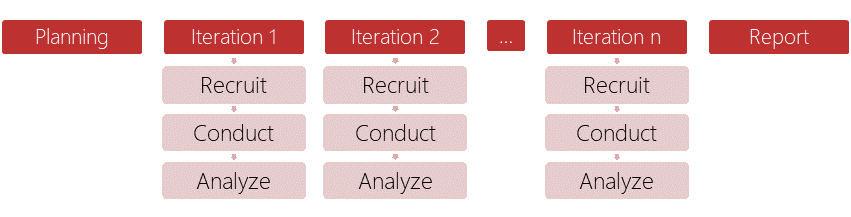

A focus group project is usually broken up into five phases:

- Planning: Where you plan the effort and design the study

- Recruiting: When you recruit participants to join the focus group

- Moderating: When you conduct the group session

- Analyzing: When you analyze the results

- Reporting: When you write up the results

As with any project planning effort, we have a lot of stuff to think through.

There are ten primary planning tasks identified by David L. Morgan (and referenced by Thackeray & Niger) in his book, Focus Groups as Qualitative Research. In this section, I’ll describe each one and propose others specifically relevant to business (and business analysis) efforts.

“Define the purpose and outcomes of the project.”

Defining what you want to get out of the project is key. It provides direction for planning and session design, certainly. But early goal definition also helps to identify situations where focus groups are not the ideal method.

“Identify the role of the sponsor in the project.”

We all know that the project sponsor is key. And we know it’s the most important relationship for Business Analysts to cultivate. But what about the focus group sponsor?

It’s the exact same thing.

If you’re running a focus group as part of a project, the project sponsor will be the focus group sponsor.

If you’re running a product-oriented focus group, the Product Manager will most likely be the focus group sponsor.

If you’re running a strategy- or enterprise-oriented focus group effort… all bets are off. There is no one right way to do this, but usually the executive sponsoring the overall effort is going to sponsor the focus groups as well.

Whatever the case, make sure you keep the sponsor aware of what’s going with the focus group efforts, and get their direction.

“Identify personnel and staffing resources.

Who will moderate the sessions? Are they properly trained and equipped to do so? Will they be able to emotionally handle negative responses from participants?

Also, who will perform the analysis? Most likely, it will be you, the Business Analyst (and that’s my assumption for the rest of this article). If so, additional training may be necessary. Alternatively, focus group consultants can be brought in to conduct the entire project or aspects of it.

“Determine who will be the participants.”

In short, who are you trying to learn about?

If you’re trying to learn how customer service reps feel about their current system, then you’ll want to run a focus group of CSRs.

If you’re trying to learn what customers think about their onboarding experience, you’ll need a bunch of customers.

More to come on this later.

“Develop a recruitment plan.”

How will you find participants? Will they be paid for their time? Or will there be another form of remuneration?

“Develop the timeline.”

Developing a schedule can be challenging for focus groups, because of their iterative nature. Let’s take a step back and look at this.

You can’t just run one focus group. Even though we are going for qualitative data, that doesn’t mean we can accept just any number of participants and any number of sessions.

Academic research has shown that a minimum of 3 to 4 sessions with at least 6 participants each is necessary before you get any reliable results.

We really only consider the effort to be complete when we reach saturation, which is when you run a session without gaining any new insights.

What does this mean? Well, consider this illustration of a phased focus group project.

It might look familiar, as it is identical in form to an iterative project lifecycle. Each iteration contains one focus group session, and we keep running them until we stop getting new data.

A very simple, barebones, and straightforward focus group project might only take six weeks (two weeks for planning; three 1-week iterations of recruiting, moderating, and analyzing; and a final week for reporting). In the real world, a typical focus group project may take months.

And this causes a problem: We rarely have months to develop requirements, let alone to execute a particular form of information-gathering. This leads us to reexamine when we should actually run business analysis focus groups. For many organizations, focus groups will make sense only for enterprise/strategy analysis and program-level analysis efforts.

“Set the locations, dates, and time for the sessions.”

Not much to say here, other than that the locations should support the various observation and recording needs of the sessions. Focus groups are typically video- and audio-recorded for later analysis.

“Write the questions in the interview guide.”

The Center for Innovation in Research and Testing have a great list of considerations for developing the interview guide, and I won’t recreate it here – you’ll have to click that link and do some more reading.

I will say that their framework of engagement, exploration, and exit questions is a godsend I wish I had found earlier in my career.

Also, their advice on specific question formats is valuable, even where it contradicts common business analysis practice (e.g. “Avoid asking why”).

Beyond this resource, two common questions pop up:

What format should the interview guide take?

There is no one format or template. In practice, we have sections (e.g. engagement, exploration) with bullet-pointed questions under each one. The only rule is that if something is important for the moderator to say… it needs to be specified in the guide.

How many questions should a focus group have?

In my experience, we typically have on the order of 7 to 15 questions. More than that, and the moderator ends up feeling rushed or the sessions go too long. Focus groups are usually around two hours long.

Don’t worry too much about how many questions there need to be. Focus instead on asking the best questions.

“Design the analysis plan.”

During the planning phase, you’ll need to answer the only high-level questions you can answer at this stage:

- Who will do the analysis?

- Are they equipped to do the analysis?

- How long will it take?

We’ll cover analysis in detail later in this article.

“Specify the elements of the final report.”

I’ve made this very easy for you, by sketching out a format below.

However, it will be up to you, your sponsor, and any other brainiacs you can assemble to make sure that it meets your needs and will achieve the goal.

To this list of planning tasks, I’ll add two of my own:

Set a budget.

Focus groups tend to require special resources:

- Will you have to hire a moderator?

- Will you have to rent a space for the sessions?

- Will you have to rent/buy video and audio recording equipment?

- Will you need to pay participants?

After figuring out these parameters, how will these resources be budgeted within the enterprise? Will they be part of a project budget?

Giving consideration to these matters in advance can also help to steer you toward cheaper methods if necessary. For this reason, budgeting should be done as early as possible, preferably right after goals are defined.

Give some thought to communications planning.

Who needs to know about focus group progress? How often? In what form? For what reason?

Management (your sponsor and others) will likely want to hear about initial outtakes before the information is analyzed and reported on. You should accommodate these requests.

Providing a few pithy quotes that are representative of the overall sense of the sessions is an appropriate way to do this. Just be sure to caution management that you have a lot of data to analyze and that the final report might vary substantially.

RECRUITING: How to set up a focus group

Garbage in; garbage out. Qualitative research is only as good as the people who participate.

It is therefore crucial that we recruit the right participants. In this section, we’ll talk about how to do it.

There has been some limited discussion (in Modern Analyst, for example) about group participants being “homogenous” vs. “heterogenous.” Let’s clarify this: They should be both.

All focus group participants should be members of the category of people that we wish to learn about (e.g. past customers, entrepreneurs, Canadian women of age 65+).

Within that population, the participants should be heterogenous – they should be representative of the population they represent.

During the planning phase, you identified that larger population that you want to learn about (e.g. users, customers). Now that we’re getting into the recruiting phase, it’s time to figure out who to include.

Here’s my process:

Determine which segments of the population you wish to analyze

Let’s say we want to gauge employee sentiment about a new clean desk policy.

We would want to get data from people who work in offices vs. those who work in cubicles.

We would want to learn about people who usually work from home vs. in the office.

We would want to learn about people who travel more than 25% of the time vs. those who don’t.

And the list likely will go on.

Each of these aspects represents a different segment of the employee population. We will need to recruit office-workers, cube-workers, and home-workers. We’ll need frequent travelers and non-.

The point of this segmentation is to give us the ability to develop analytical insights later, in addition to making sure that we’re getting the heterogeneity we discussed earlier.

Determine your participation criteria

Sometimes, you will need to establish certain parameters that all members of the population must have (beyond simply being members). And sometimes you will need to exclude population members with certain attributes.

For example, you might need to exclude power users from usability studies, or brand new customers if a certain level of experience is required.

Invite people to participate

There are many different ways to do the actual recruiting, and they all hinge around who your population is.

If you are studying customers or users, you will probably e-mail them. Same deal with fellow employees. However, if the people you’re reaching out to aren’t known to you (the organization), it’s a bit trickier.

One recent trend has been to use social media advertising to find participants. This can create some bias, yes, but these platforms more than make up for it with segmentation capabilities (e.g. men, aged 25 to 34, living in the Washington DC metro area, with salaries greater than $75K, with expressed interest in backpacking).

Follow up with them as necessary

Every once in a while, you will invite someone to participate in a focus group; they will accept; and then they will show up. God bless that person.

Everyone else? You’ll have to follow up with reminders. Don’t overwhelm them; just make sure they’re aware.

If you have a typical consumer participant base, reminders 7, 3, 2, and 1 days before the session should suffice. If you have executives or doctors or other exceptionally busy people, I’ll recommend reminders 14, 7, 3, 2, and 1 days before.

Wrapping Up

So this is the core of what you need to know about setting up, planning, and recruiting for focus groups as a Business Analyst.

Soon, we’ll update it further with critical advice around moderating groups, analyzing the results, and making the final report.

How about you?

What challenges or limitations have you run into with focus groups?